ToK Essay 5 Nov 23: "The world is the way we understand it"

“the world isn’t just the way it is, it is how we understand it—and in understanding something, we bring something to it” (adapted from Life of Pi by Yann Martel)?

Is this always the case ?

Discuss with reference to history and the natural sciences.

So at the start of the this essay we have a clear proposition that the world is constructed or created by our processes of understanding it. In philosophy this is called a rationalist argument, however you don't necessarily need (or want) to refer to the philosophical debate between rationalism and empiricism. That said this debate will very much underpin the discussion that I bring to this essay.

Let's start by quickly looking at some of the interesting words used in the prescribed title, and the first phrase of Interest here is the world isn't just the way it is. the use of the isn't just and later use of the phrase bring something to it, would indicate that the human construction of knowledge is an additive process, i.e. we add to that which is gained from the senses rather than essentially alter, or change, it.

The use of the term understanding in the quote indicates that this process is one in which we bring meaning to the world that is presented to us. This is a rich area for further discussion in the essay should students choose to take this route.

ToK Essay 5 Nov 23 - a few overview arguments

In these overview notes we will quickly and broadly look at to arguments for supporting the proposition in the prescribed title, and to arguments evaluating or opposing the proposition in the prescribed title. in the essay guidance notes “10 Arguments for essay #5 “ we go into a lot more detail on 10 arguments including knowledge arguments, evaluations or counterclaims, suggestions for real life situations, and implications arising from the knowledge arguments. Those notes are over 8,300 words long and give you a lot more than can be achieved in this web page.

ToK Essay 5 Nov 23 - interpretation

Argument one for the proposition could be that The interpretation that we bring to the world doesn't radically change the external reality so much as give it internal meaning. This argument could be applied to either AoK History or AoK Natural Sciences. The essential argument here is that our additive interpretation (understanding) doesn’t radically change the world, but just makes it gives it a representative meaning so that we can label it and categorise it within pre-existing knowledge frameworks. Students who have studied Knowledge and Language as an optional theme can draw upon some of the debates covered in that unit.

This argument is easier to apply to AOK Natural Sciences than it is to AOK history. in Natural Sciences we would be arguing that the scientific method produces objective and accurate data about an external reality, and then human interpretation of that data retains the essential features and characteristics of that external reality. To apply this argument to AoK history we need to develop an understanding of a process which minimise the role of perspective and subjective biases in the historiographical process. Well this is a hard argument to make, it is not an impossible argument. Students following this argument may want to look at the production of historical knowledge as a process of empiricism. This is explored in a lot more detail in the essay guidance notes.

ToK Essay 5 Nov 23 - interpretation (different perspective)

Argument two is that the world we experience is largely an interpreted world rather than a real world. in philosophy this would be called irrationalism however you don't have to use this term in your essay. The argument here is that we select, group, label, categorise, and add meaning, to the experiences of the world. As such we fundamentally change what we know about the world around us.

This argument can be applied to both AOK history and AoK Natural Sciences. however it is far more straightforward to apply to AOK history. Students who would like to follow this route should consider looking at history as a product of human construction, or history as a rationalist process. The argument in history is a constructionist argument that we select specific historical knowledge, and interpret it in ways that serve pre-existing knowledge, to confirm a preferred world view. The arguments in the Natural Sciences would be that the operationalization of variables and the interpretation of scientific result fundamentally changes that which is observed. again, we go into this in a lot more detail in the detailed essay guidance notes .

ToK Essay 5 Nov 23 - reality

Turning towards arguments against the proposition in the prescribed title. The first arguments would be that the external world is how we experience it, we do not add things in through interpretation. As such we are arguing that our knowledge of the world is objective and accurate. This is an empiricist argument (however you do not have to use that term in your essay). This argument could be used both for AOK history and AOK Natural Sciences, however it is far easier to make for AOK natural sciences. The hypothetical deductive scientific method is essentially an empirical method which is designed to minimize human interpretation and subjectivity.

ToK Essay 5 Nov 23 - context

The final argument covered here, concerns the role of context in our understanding of the world. An argument could be developed that the degree to which we interpret external reality is dependent upon the context of the knower, and the knowledge that they are acquiring at that time. Context can include a very wide range of factors including the cultural perspectives of the knower, the intention and purpose of the knower, the type of knowledge that is being acquired, and the pre-existing knowledge frameworks.

This argument lends itself particularly well to AOK history, but can also be applied in AOK natural sciences. Contrasts could be drawn using real life situations in AoK history. We could consider historical knowledge which has been produced for different purposes, or within different cultures, or by historians with different perspectives. This will show the role of context influencing the different ways that the same historical event has meaning (“understanding”) attached to it. This argument is developed and a lot more detail, including real life examples that you could draw upon, in the detailed guidance essay notes.

We also have 25 questions that you could ask artificial intelligence (such as ChatGPT, or Bard) to help you to write this essay.

This is just a brief overview of four of the arguments that could be used in this essay. Our detailed guidance notes have a lot more detail on these, and six other arguments.

ToK Essay #4 Nov 23: Values problematic

PT#4Nov23: Is it problematic that knowledge can be shaped by the values of knowledge producers ?Discuss with reference to any two areas of knowledge.

Choice of AoK

You have the choice of any areas of knowledge, therefore We recommend that you choose two areas that have good contrasting methodologies in the production of knowledge. you're going to be looking at the influence of values on the production of knowledge and therefore the role of the knowledge producer will be crucial. if they have different roles then you can contrast the influence of values. a typical good contrast might be between area of knowledge the Arts and area of knowledge natural science.

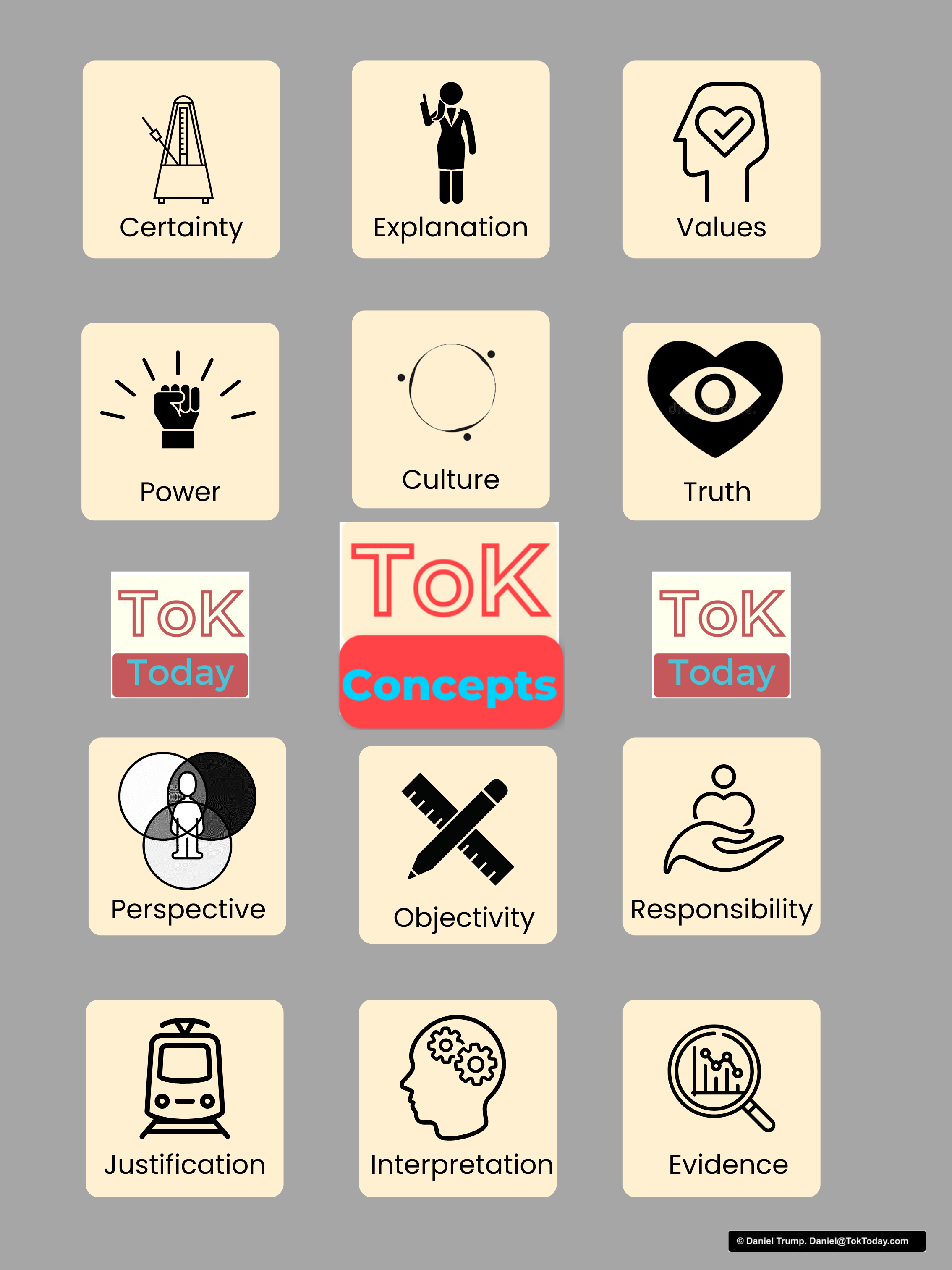

ToK Concepts

This essay lends itself perfectly to the use of the 12 ToK Concepts.The May 2022 subject report recommends that students use the concepts in their essays. any of the 12 Concepts can be applied in this essay. I have outlined four of the concepts below, and I go into the details of 10 of the concepts in the essay guidance notes 10 arguments for essay number four, available at this link.

Problematic

Students will need to define the term problematic or problem as it's at the center of the prescribed title. you may want to think about who is defining the idea that it may be a problem, what type of a problem, a problem for whom, or what? you may also want to consider whether problems are universal or context bound, Etc

Let's move on to look at how four of the ToK Concepts could be used to answer this prescribed title.

Interpretation

In any area of knowledge the knowledge producer interprets many stages of the knowledge production process including the object to be produced, the way in which it is to be produced, and the evidence arising from the method of production. the ways in which knowledge is produced varies by area of knowledge and knowledge producer but it all includes interpretation. the important thing about interpretation is that it is informed by values. the values of the knowledge producer influence the way in which all stages of the knowledge production process are interpreted. This argument can be developed in various ways depending upon the area of knowledge chosen.

Whether the interpretation of value-based knowledge is a problem or not depends upon a range of factors such as the values held by the person who is interpreting the knowledge, the values of the context within which the knowledge is interpreted, and interpretation of the purpose of the knowledge and it's alignment with the knower.

(I go into a lot more detail on this, including real life examples, in the essay Guidance Notes).

Culture

Culture could be described as a set of values, interwoven with a system of Symbols and meanings. as such, a fairly coherent argument can be developed that culture (& cultural values) influences the production of knowledge. Whether the influence of cultural values is a problem very much depends upon a wide range of issues including the cultural alignment of the person who is defining the problem, the culturally defined purpose and value of the knowledge produced, and the resultant evolution of culture over time resulting from the knowledge produced.

Evidence

The values of the knowledge producer can affect both the production, identification and interpretation of evidence. that which is considered evidence is, arguably, very much influenced by the values of the person considering it. Different areas of knowledge place different emphases on the nature of evidence, different types of knowledge constitute evidence in different ways according to the area of knowledge. As such, students who are writing this essay could contrast what evidence looks like in for example AoK mathematics with what evidence looks like in for example AoK The Arts.

Potentially this is problematic in terms of the objectivity and purpose of the knowledge produced. Again, this will very much depend upon the values of the person who is making the judgement on whether it is problematic.

Justification

Arguably values influence the justification for producing new knowledge, and then the justification for the use of that new knowledge. such justification may be based upon the values of the knowledge producer, the institution to which they may be long, the academic discipline that they are working in, or wider society. values based justification is potentially problematic for a range of reasons including the hierarchical use of knowledge for the articulation of power, Producing biased perspectives, and disregarding aspects of knowledge. In a typical ends versus means type argument justification can lead to legitimisation, if the values underpinning the justification are not shared by a large sector of society this could be problematic at ethical, moral and cohesive levels.

The Essay Guidance notes "10 Arguments for essay 4" go into a lot more detail on the four concepts above, and on six other concepts. Those notes also include

definitions of terms

real life examples

evaluation

implication points.

ToK Essay 3 Nov 23 "Dangerous Experts"

ToK Essay 3 Nov 23 "Dangerous Experts":

In the acquisition of knowledge, is unquestioningly following experts just as dangerous as completely ignoring them? Discuss with reference to the human sciences and one other area of knowledge.

The Acquisition of knowledge is generally taken as gaining knowledge, or becoming knowledgeable. Whilst this term is not defined in the ToK Study guide it can be assumed that it refers to the process of becoming a knower. Learning, in both formal and informal senses, is a process of knowledge acquisition.

Choice of Area of Knowledge - ToK Essay 3 Nov 23 Dangerous Experts.

You are directed to use Human Sciences, and are given a free choice on the other AoK. You may want to pick an AoK which gives a contrast to ways of acquiring knowledge in Human Sciences as your second AoK. This could also be (indirectly) linked to a contrast method of producing knowledge. Consider whether ways of acquiring knowledge in AoK Maths, History or The Arts contrasts well with AoK Human Sciences ? A good contrast in the processes of acquiring knowledge will give you greater potential for developing good evaluation, and implication, points in the essay.

A hard choice.

We are offered a choice between “following unquestioningly” or “ignoring completely”. Obviously we want to sometimes accept, sometimes ignore, sometimes accept critically, and sometimes ignore in an informed manner. However, these choices are not given to us. It is advised that students directly address the choices given in the PT before arguing for any of the nuanced positions between these two choices. You will need to explain to the examiner why you are rejecting the two positions given if you want to argue for an ‘in-between’ position.

Further, the focus of the question is actually asking us which is the more dangerous of the two choices given. As such, we can assume that the safer nuanced (in between) position is less important than the relative dangers posed by the two positions given. It is advised that students focus discussion on the relative dangers of the two positions rather than the in-between preferred positions.

Experts

Consider who these ‘experts’ are in each area of knowledge. Questions that could lead to knowledge points include:

How did they become to be labelled as ‘experts’ ?

Do ‘experts’ all share the same perspective in a discipline / AoK ?

Are there competing ‘experts’ ?

Why are they labelled ‘experts’ ?

Are we considering the expert themselves, or their knowledge ?

Danger.

You will need to think about what these ‘dangers’ are that could arise from following / completely ignoring these experts. Danger to what / whom ? Danger for what ? You may want to consider the development of the Area of Knowledge, the type of knowledge produced, or the uses of that knowledge. There can be obvious links to ethics here, which could be contrasted with arguments regarding objectivity.

Objectivity.

In directing us to consider AoK Human Sciences we are offered the opportunity to consider the function / purposes of the Human Sciences. This is a rich area for debate and discussion. There is a potential debate between the objectivity of the Human Sciences vs the ethical implications of knowledge developed in the Human Sciences. If you study Economics, Environmental Systems, Geography or Psychology this debate will be evident to you. Students taking Business Management can also develop such debates regarding ethical business practices etc. This is an area where there are clear opportunities for you to draw upon the content of your Group 3 Diploma Subject. Ask your Grp 3 teacher for advice if you are unsure of the debate between ethics and objectivity in your essay.

Ethics.

The discussion concerning ethics could occur at 2 levels:

(i) The ethical consequences of ignoring / unquestioningly accepting the application of the knowledge that experts produce.

(ii) The ethical consequences for the development of knowledge in the discipline / AoK of ignoring / unquestioningly accepting the knowledge that experts produce.

Context

The context of the expert’s knowledge, the acceptance / rejection of experts, and the application of the expert’s knowledge will change. As such the dangers posed by accepting / rejecting experts will also change. This provides a rich seam of discussion in any area of knowledge. Context provides great evaluation and implication points for any Area of Knowledge.

Confirmation Bias

Following people unquestioningly, and ignoring them completely, potentially gives rise to a range of fallacies (see this post on fallacies), particularly confirmation bias. Any AoK can give great opportunity for a discussion on confirmation bias in the acquisition of knowledge, and its consequences for the development of biased perspectives of the knower.

Foundational / Definitive Knowledge.

There is a potential discussion around the scope, or definition, of a discipline / AoK. Is there a set of ‘expert knowledge’ which must be acquired in order to develop an understanding of that discipline ? For example, can you study economics without learning about theoretical vs empirical models, Macro & Micro Economics, Pluralist vs Free Market models etc ? Obviously economics students are not taught to accept this knowledge ‘unquestioningly’, they are taught how to evaluate this knowledge. However, arguably they are following the evaluative knowledge unquestioningly as well…,

Innovation / development of new knowledge

One way of thinking about AoKs is whether the acquisition of knowledge in that AoK is more “top-down” or “bottom-up”. Top-down processes are more hierarchical in which the knower is discouraged from developing critical, personal, perspectives. Bottom up processes of acquisition are led more by enquiry, in which the knower is encouraged to develop their own perspectives. Contrasting two AoKs in this way will allow the student to develop an argument about the dangers which may be inherent to, or arise from, either type of knowledge acquisition process.

These arguments, and many more developed in far more detail in the notes: 10 Arguments for ToK Essay #3 available from TokToday - those notes contain

knowledge arguments

evaluation points

Implications of knowledge arguments

suggested real life situations (with references)

We also have a list of 25 questions that you can ask Artificial Intelligence (such as ChatGPT) about ToK Essay #3. These questions are designed to get relevant content which is appropriate for this ToK Essay.

ToK Essay 2 Nov 23: Beautiful Patterns

PT#2 N23 If “the mathematician’s patterns, like the painter’s and the poet’s, must be beautiful” - what would be the impact on the production of mathematic and artistic knowledge?”

ToK Essay 2 Nov 23 beautiful patterns:

This question could be approached as a consideration of the ways in which knowledge is made (produced, constructed, discovered) rather than about the knowledge itself. The PT does direct us to consider the “impact on the production of knowledge”.

Beautiful subject rather than object.

If it’s about the production of knowledge, rather than the knowledge produced, its about subject rather than object. The word “beauty” could lead a lot of people to think that it’s about the object of knowledge production, however we’d advise students to focus on subject rather than object.

Obviously, subject and object are linked, and the former may lead to the latter. Maybe a good place to start is to think about the reasons why mathematicians make knowledge, and compare it with the possible reasons for artists making knowledge.

Purposes of knowledge production.

There’s potentially a nice contrast in the purposes for knowledge production in The Arts and Mathematics. We could compare the debate in Mathematics between Pure and Applied Maths with the debate in The Arts over whether artists make knowledge for themselves or for their audience.

That debate in Maths would be that Pure Maths is made purely to extend mathematical knowledge, whilst Applied Maths is made to solve real world problems. Conversely, the debate in the Arts would be that some art is made just for the artist to express their inner world, whilst other art is made to engage the audience (“the knower”).

Link "beautiful patterns" and interpretation.

Beauty is often thought of as a relativist concept (“beauty is in the eye of the holder”).

We’d advise students to be wary of relativist arguments as they are rarely sufficient to attract high marks in the ToK Essay.

Potentially, a more substantial argument would be that true beauty in the production of knowledge should be free from / independent of external constraints such as audience preferences in the arts, and real world problems in Mathematics.

A further argument could be developed around the role of interpretation in the production of knowledge. Processes of interpretation of knowledge in the arts could change both how patterns are identified and how they are used in the production of knowledge.

As such the role of interpretation in the production of artistic knowledge could change the explanations, justifications and perspectives pertaining to that knowledge - which in itself could change the definition and attribution of beauty.

In Maths the interpretation of pre-existing knowledge (e.g. axioms, theorems and models) could affect both the justifications and evidence used by mathematicians. This could be further applied to the discussion of the relationship between forms, objects and theorems in Maths.

The role of context in the production of (beautiful) mathematical and artistic knowledge.

There’s a really interesting debate to be had about whether the patterns are merely context bound, or are they universal. This debate could be developed to consider whether beauty is also context bound or universal. This could be further developed to consider whether the methodologies of knowledge production are context bound or universal.

If the patterns, beauty and even the methodology are context bound then there may not be an underlying near aesthetic structure to mathematical and artistic knowledge (as implied by Mr Hardy) because that definition of beauty is ever changing.

These arguments, and many more developed in far more detail in the notes: 10 Arguments for ToK Essay #2 available from TokToday - those notes contain

Over 9000 words of ToK content.

knowledge arguments

evaluation points

Implications of knowledge arguments

suggested real life situations (with references)

We also have a list of 25 questions that you can ask Artificial Intelligence (such as ChatGPT) about ToK Essay #2. These questions are designed to get relevant content which is appropriate for this ToK Essay.

Essay 1 Nov 23: Facts alone - Enough?

ToK Essay 1 Nov 23 Facts alone - are they enough to prove a claim ? This question gives you the freedom to choose any two areas of knowledge to discuss. Choose wisely as this will make writing the essay far easier.

Structure - it's a fact!

Students are advised to choose two areas of knowledge which give them good contrasts in both the production of knowledge, and have contrasting methodologies for proving claims.

If your two areas of knowledge differ a lot in these areas then it will be easier to develop evaluation points (giving you higher marks in your ToK essay).

In this essay we’re going to try to develop a continuum of arguments. We want to make some arguments that facts are enough to prove claims. In doing so we’re going to be interested in different ways of proving claims, different types of proof, and varying definitions of proof.

We are also going to want to make some arguments that facts are not enough to prove claims, and we’ll consider what other things might be needed to prove claims (and in doing so we’re going to bring in ToK concepts like evidence, justification, interpretation and maybe even TRUTH).

The command term is “Discuss”, therefore you need to consider different perspectives in the essay. (We have produced 10 Arguments for Essay #1 November 2023 that cover a range of different knowledge arguments that could be used - you can pick those notes up from this link).

What makes a fact: necessary or sufficient?

We could think about this question in terms of whether facts are necessary or sufficient to prove a claim. At a more sophisticated level we could consider what is necessary, and what is sufficient, to establish a fact in the first place.

Necessary conditions are conditions that must be met in order for a particular outcome to occur, while sufficient conditions are conditions that, if met, will guarantee that the outcome will occur. Here are some examples that illustrate the difference between necessary and sufficient conditions:

Necessary but not sufficient: In order to pass a maths test, it is necessary to know the material. However, knowing the material is not sufficient to guarantee that one will pass the test. Other factors, such as test-taking skills and time management, may also be necessary to pass the test.

Sufficient but not necessary: If a person has a college degree, it may be sufficient to qualify for a particular job. However, having a college degree is not a necessary condition for all jobs, as some may require other qualifications or skills.

Both necessary and sufficient: In order to become a licensed physician, it is both necessary and sufficient to graduate from medical school and complete a residency program. This means that without completing these requirements, one cannot become a licensed physician, and completing them guarantees that one will become a licensed physician.

Neither necessary nor sufficient: Having a driver's licence is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for owning a car. While having a licence may be helpful, it is not necessary as some people may choose to hire a driver or use public transportation. Additionally, having a licence is not sufficient as owning a car also requires purchasing or leasing a vehicle.

Applying different types of facts to Areas of Knowledge

Setting up the different conditions for what is sufficient, and what is necessary, to prove a claim can change whether a claim is proven. Different Areas of Knowledge will have different criteria for defining what is necessary, and what is sufficient, for proof. Do these constitute "facts alone?"

Turning to some of the arguments that facts alone are not sufficient to prove a claim. When we look at some of the more qualitative Areas of Knowledge such as The Arts or History, facts are not quite as definitive as they are in the Sciences or Maths. This can give us a bit more freedom to debate whether facts can stand alone as proof of a claim.

In both AoK The Arts and AoK History we could have a good discussion about what a fact is, you could consider:

Who is constructing the fact.

Their intention / purpose for constructing it.

Who validates it as a fact.

What knowledge was included, and what was excluded in the establishment of the fact.

What are the perspectives which both led to, and arise from, the fact.

What values underlie the fact.

If you follow this argument you need to remember that the essay title is not whether facts exist, but whether they can be used alone to prove a claim. As such, this argument is that no fact exists entirely on its own, but all facts are subject to a knowledge construction process, and the degree to which a fact proves something depends upon the degree to which the knowledge production process is accepted as objective.

The role of perspectives is crucial in the construction of facts in both AoK The Arts and AoK History. Further, different methods of knowledge construction can produce different facts. This means that maybe different types of proof are needed for different types of evidence, maybe we could have differing thresholds of proof, or maybe proof isn’t possible at all, despite the so-called “facts”. We could consider this in terms of a hierarchical construction of proof in a power based value system

These arguments can also apply to AoK Maths, Human Sciences, and Natural Sciences.

Considering AoK The Arts in a bit more detail. We may want to consider what constitutes a fact in artistic knowledge. Is the meaning of artistic knowledge decided by the audience or by the artist?

Knowledge arguments could be developed around the connotation and denotation of knowledge. Part of the essay could be based on the debate between artistic knowledge as object vs artistic knowledge as a process of subject.

The role of context in the production of knowledge (in any AoK) could also be considered. Context can be applied to any of the areas of knowledge, it can change both the definition and labelling of facts, the production of knowledge, and the interpretation of knowledge. Context opens up a range of ToK concepts such as Culture, Interpretation, Justification, Explanation and Objectivity.

This is just a very brief overview of a few of the issues that we explore in detail in 10 Knowledge Arguments for Essay#1 November 23. Those notes give you:

detailed knowledge arguments

definitions of terms

evaluation points

implications

suggestions for real life situations.

Those notes are over 10,000 words long, so there’s more than enough there to help you with your essay.

Secondly, We have “25 questions for Chat GPT to help you with your ToK Essay”. IB are allowing you to use ChatGPT (and other AI’s) in your ToK Essay, so long as you properly reference content that it produces. The thing with ChatGPT is that you have to know exactly the right questions to ask it to get the right content and answers out of it. This document will help you to ask it the right questions.

Fallacies in ToK

In ToK we are concerned with questions such as how knowledge is acquired, the nature of truth, and the extent of our knowledge. One of the key challenges in ToK is identifying and avoiding fallacies – errors in reasoning that can lead us to false conclusions. In this blog post, we will explore the main types of fallacies found in ToK.

1. Ad Hominem Fallacy

The ad hominem fallacy is a type of fallacy in which the arguer attacks the person making the argument rather than the argument itself. In ToK, this fallacy might take the form of dismissing an argument because of the person making it rather than addressing the merits of the argument. For example, if someone argues that climate change is real, and someone else dismisses the argument by saying that the person making the argument is a liberal, that would be an ad hominem fallacy.

2. Straw Man Fallacy

The straw man fallacy is a type of fallacy in which the arguer misrepresents the opponent's argument in order to make it easier to attack. In ToK, this might occur when someone misrepresents an opposing view in order to make their own view appear stronger. For example, if someone argues that atheism is the belief that there is no god, and an atheist argues that atheism is simply the absence of belief in a god, the theist would be committing a straw man fallacy by misrepresenting the atheist's position.

3. Appeal to Authority Fallacy

The appeal to authority fallacy is a type of fallacy in which the arguer cites an authority figure in order to support their argument, without providing any further evidence or argumentation. In ToK, this might occur when someone argues that a particular belief is true simply because an expert or authority figure says it is true. However, this is not a valid argument, as experts and authority figures can also be wrong or biased.

4. False Dilemma Fallacy

The false dilemma fallacy is a type of fallacy in which the arguer presents only two options as though they are the only options, when in fact there may be other possibilities. In ToK, this might occur when someone argues that either science or religion can provide us with the truth about the world, ignoring the possibility that both may be useful in different ways.

5. Circular Reasoning Fallacy

The circular reasoning fallacy is a type of fallacy in which the arguer uses the conclusion of the argument as one of the premises. In ToK, this might occur when someone argues that a particular belief is true because it is supported by scripture, and then uses the belief in scripture as evidence for the truth of the belief. This is not a valid argument, as it simply assumes the truth of the conclusion.

In conclusion, fallacies can be a major obstacle to gaining knowledge and understanding in ToK. By being aware of the most common types of fallacies, we can better identify them and avoid them in our own reasoning and arguments. This, in turn, can help us to arrive at more accurate and well-supported conclusions about Knowledge acquisition and production.

Daniel, Lisbon, March 2023

Are all swans white? (Falsification)

The Principle of Falsification in Theory of Knowledge

The Falsification Principle is a method used in science to test the validity of scientific statements or theories. It was first introduced by philosopher Karl Popper, who argued that scientific knowledge must be testable and falsifiable, meaning that it must be possible to demonstrate that it is false. In other words, a scientific statement or theory can only be considered true if it is possible to prove it false.

To illustrate the Falsification Principle, let us consider the statement "all swans are white". If this statement is true, then every swan that has ever existed or will exist must be white. However, this statement can be falsified if just one black swan is found. The discovery of a black swan would prove that the statement "all swans are white" is false, as it would contradict the statement's claim that all swans are white. This example demonstrates the power of the Falsification Principle, as it shows how a single observation can disprove a theory or statement.

The Falsification Principle is important for establishing objective knowledge in science because it provides a way to test scientific statements and theories. By attempting to falsify a theory, scientists can determine whether it is true or not. If a theory withstands numerous attempts at falsification, it becomes more likely to be true. This process of testing and refining scientific knowledge helps to establish a strong foundation of objective knowledge that can be relied upon for future research.

One of the key benefits of the Falsification Principle is that it prevents scientists from making unfalsifiable claims. An unfalsifiable claim is one that cannot be proven false, and therefore cannot be tested using the scientific method. For example, the claim that "God exists" is unfalsifiable, as it is not possible to prove that God does not exist. Since this claim cannot be tested, it falls outside the realm of science.

The Falsification Principle also helps to prevent scientists from making unjustified claims. By requiring that scientific statements and theories be testable and falsifiable, the Falsification Principle ensures that human and natural scientists do not make claims that cannot be supported by evidence. This helps to maintain the integrity of scientific research and ensures that scientific knowledge is based on sound evidence.

In conclusion, the Falsification Principle is an important tool in AoK Human Science and Natural Science for establishing objective knowledge. By requiring that scientific statements and theories be testable and falsifiable, the Falsification Principle ensures that scientific knowledge is based on sound evidence and prevents scientists from making unfalsifiable or unjustified claims. The example of "all swans are white" demonstrates how the Falsification Principle can be used to test scientific statements and theories, and how it can help to establish a strong foundation of objective knowledge in science.

Daniel, Lisbon, March 2023

Further related posts can be found at:

Priest's religious knowledge - do they believe in God?

Today's post can be used as an RLS for The Core Theme Knowledge & The Knower, and as RLS for AoK Human Sciences, and the Optional Theme Knowledge and Religion. It's about Priests who don't believe in God, and was the most popular post on my old ToK Blog (ToKTrump). There are obvious links with the role of Religious Knowledge in this research.

The Core Theme: Knowledge and The Knower is a very broad unit encompassing a wide range of knowledge questions. It can be a little unwieldy if not focussed onto some key knowledge questions, or a set of themes. I have slowly developed a sense that my student's most illuminating learning in this unit is firstly that knowledge is constructed rather than give, secondly that that process of construction is highly contextualised, and finally that it is not experienced as contextualised by the knower.

It's difficult to find the original study today, however I did find:

A review in The Atheist's Quarterly on JSTOR linked.

A summary on the website Why Evolution is True linked.

The world view of the knower is not experienced as contextualised, but is their "known world". We can draw upon Husserl's view of "Lebenswelt" or lived world here.

Why is The Priests who don't believe in God pertinent to ToK ?

Unstructured interviews of 5 non-believing priests carried out by Dennett & LaScola (2010) are a fascinating, and rare, insight into people who hold one set of beliefs, and yet live their lives by another set of beliefs. This dissonant state gives rise to a compelling set of insights for ToK. Whilst this example may not be 'typical' for most knowers, arguably it is in this somewhat extreme, contrast that we can uncover some of the processes of knowing that are experienced by all of us as knowers. Some of these implications include:

We can hold contradictory knowledge (and beliefs) at the same time.

Performativity of knowledge is both evidential and significant ( a behavioural element of knowledge).

Internal ethical justification of knowledge occurs when the knower is presented with contradictory or inimical knowledge/beliefs/values.

Even deeply held beliefs and values can change when the knower is challenged with opposing arguments/beliefs/values.

When deeply held beliefs/values are changed the knower may not change their public behaviours according to the newly held beliefs.

Beliefs & values (as forms of knowledge) can be known in many different ways by different knowers.

How to use this in ToK:

Core Theme: Knowledge & The Knower.

A quick skim through the KQs of the Core theme Knowledge & The Knower we can immediately see links to many KQs, particularly those dealing with the knower's knowledge in relation to others through interactions. I have allocated KQs to groups of students and asked them to use the research to explore their allocated KQ.

AoK Human Sciences.

The study can be relevant to all of the Hum Sci Knowledge Framework. Of particular interest to me is the link to perspectives and research methods. Specifically the validity vs reliability debate, and the value of extrapolation from a small (& we assume unrepresentative) sample.

Optional Theme - Knowledge & Religion.

Obviously there are a range of interesting KQs which could be explored using the Dennett & La Scola study. Of particular interest is the link between faith & religious beliefs, the role of culture's influence on religious beliefs, the relationship between reason and religious beliefs, etc.

For more ToK Lesson content for Knowledge and the Knower try this link.

For more ToK Lesson content on AoK Human Sciences try this link.

Conclusion.

The Dennett & LaScola research focuses on an atypical and unusual situation in knowledge. However, maybe it is in the strong contrasts found in the unusual cases that we can better understanding the framework and underlying processes of the knowledge held in all other cases.

If you would like more content like this (focussing on useful RLS), or have suggestions for further content please don't hesitate to contact me - Daniel@TokToday.com

Wishing you a great day!

Daniel, Lisbon, Jan 2023

Bibliography & References.

“Atheists Anonymous.” The Wilson Quarterly (1976-), vol. 34, no. 3, 2010, pp. 77–78. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41000971. Accessed 11 Jan. 2023.

whyevolutionistrue. “Dennett and LaScola Study of Nonbelieving Clergy.” Why Evolution Is True, 18 Mar. 2010, whyevolutionistrue.com/2010/03/18/dennett-and-lascola-study-on-nonbelieving-clergy/. Accessed 11 Jan. 2023.

Choosing your ToK Essay Question

As the November 2023 ToK Essay title starts it is a good time to revisit advice on choosing your ToK Essay title. During the 10 years that I marked ToK Essays as an IB Examiner I learned a lot about what makes a good ToK Essay. More importantly, how students can write a good essay with minimum stress.

Choosing your ToK Essay Question.

The questions are called "Prescribed Titles"(aka PT), as they're not actually questions per se. They are knowledge statements, or knowledge questions, which you are invited to "discuss". This means that you need to consider a range of different perspectives arising from the title. When choosing your ToK Essay Question consider whether you have (or can develop) a range of perspectives on the title.

Do not change, nor amend, a single word of the PT. You must address the question exactly as IB give it to you.

Ensure that you get the exact title from your teacher. Non-IB Sites (such as TokToday) are not supposed to publish the exact titles (they're copyrighted by IB).

Take your time choosing.

Choosing the ToK Essay title which is right for you is at least 50% of the 'battle for success' in the ToK Essay, so take your time at this stage. My students spend 4-6 weeks on choosing the title, it's super important to get this stage correct. In deciding which title to write you are should be trying to clarify:

What does this question mean to me ?

Do I have an initial instinctive view about this question ?

Do I have some ideas about arguments that would help me to answer this question ?

Do I have a destination for my answer ? (this may change later on, but something at an initial stage will be helpful).

These questions smoothly segue into our second tip on how to choose your ToK Essay Question: Blank Slate.

Know Yourself: Blank Slate those titles.

Try not to be too influenced by other people's voices at this stage of your essay writing process, try to hear your own voice.

Know your own mind, try not to be influenced by the voices of others. Approach the titles as a 'blank slate' - ie no pre-judgment.

Eventually you will have to write your own, original, response to the question. Therefore you don't want to be too influenced by other people's views at this stage (you can explore their views later). You need to be developing your own view(s) at this stage.

Be original.

Many of the best essays that I have read have been where the student developed their own original, and quite novel, argument at this early stage. Now, it may seem rather self defeating for me to tell you to stay away from internet advice sites either before or during the essay, however the particular type of content that I think you should be wary of is content that tells you what the arguments (claims / counterclaims) could/should be, or what real life examples you should use. This directive content doesn't improve your skills & understanding in ToK because you don't have to think for yourself.

Develop your own arguments, and think of possible real life examples to illustrate these arguments, before you start exploring the internet. Once you have your own original framework down you'll be in a good place to start further research. You can now use academic sources, non-academic sources and ToK specific sources to further develop your ideas and range of sources cited. If you wait until you have developed your own ideas before you go to the Internet (& other sources) then you won't be negatively influenced / swayed by the sources that you find. By developing your own ideas you will find writing the essay far easier than trying to develop other peoples ideas. This is why it's so important to spend time early in the essay writing process working on your own claims counterclaims and real life examples.

Know your destination.

Before you finally decide it is useful to have a rough idea of how you will resolve that question. That is a vague idea of what your final answer to the question might be (ie your "destination"). You don't have to know exactly how you are going to resolve the question before you choose the question (as many new ideas and perspectives will be developed during the planning and writing stages.

A rough idea of destination guides the writer like it guides the walker

A rough idea of destination guides the writer, like it guides the walker.

As you write the essay you will develop new ideas, make new connections and develop new perspectives. You will refine your arguments, and you may even change your arguments. This is a normal, and healthy, aspect of the writing process. You may even change your final destination, the important thing when choosing a question - have direction and destination in mind. Far too often I meet students who are "stuck", usually because they are unsure of their approximate final destination. They didn't work on a solution or resolution before they chose a question. - not a good place to be.

A few 'easy ways' to check your understanding of the title:

Explain the question to a non-ToK student.

Bring in your Mum, Dad, sibling (or even dog) and explain the title to them.

When they can understand your explanation you can be sure that you now have a solid understanding of the question.

More help is available:

Check out the ToKToday YouTube Channel for tips (especially the Student Playlist).

Pick up the E-book How to Write the ToK Essay in 6 Easy Steps.

If you need more help to choose your question, or to develop your question then get in touch (daniel@toktoday.com). Click here to book a ToK Coaching session.

Daniel,

Lisboa, Portugal, March 2023

Reflections on May 23 ToK Essay Session

I’ve been working with many students from all over the world with their May 23 ToK Essays. This post is partly a consolidation of reflection for me, but it should also be useful for other ToK teachers, and maybe for ToK students who are about to start their learning.

Why write reflections on M23 ToK Essay session ? Well, I’ve been working with many students from all over the world with their May 23 ToK Essays. This is the first time that I’ve worked with students who are not in my school, nor in my ToK class. And that's an interesting learning experience for me - because I don’t know what they’ve been taught, how they’ve been taught, what their teacher’s approach to ToK is, nor where the emphases and reference points are in their ToK knowledge. So, this post is partly a consolidation of reflection for me, but it should also be useful for other ToK teachers, and maybe for ToK students who are about to start their learning.

In essence, in this essay session I’ve gone from Goffman’s participant-observer to observer-participant.

So, what are the reflections on M23 ToK Essay Session (main learning points) ?:

1. Making or building the argument.

A significant issue for many of the students with whom I worked was that they lacked the skills, or knowledge, to build a ToK argument. And this causes many consequent issues. It leads to:

Problems with definitions, I heard a lot of questions such as - “How do I define this key term ? or that key term?” , “I can’t think of a definition for…,” etc

Developing claims or counterclaims, I got questions such as “I can;t think of a counterclaim for this”, or “how can I make this into a claim ?”

And finally problems with identifying RLS - “is this a good RLS for____?”

These 3 problems (definitions, claims/counterclaims, and RLS) come from not having the skills to build a knowledge argument. Let me, briefly, take each one in turn.

Definitions:

In this session we wrangled with definition such as “cannot be explained”, “replicability”, “bubbles” etc

Obviously students should not be using dictionary definitions, but some students are still using dictionary definitions. The definitions are often the basis of the whole essay, if you can’t develop the definitions then writing the essay is problematic.

There’s a mutually reciprocal relationship between developing the definitions of key terms and devising the knowledge claims / counterclaims.

There's also the problem of some students rewriting the key concepts - I particularly saw this with essay #2 - the vast majority of students I worked with doing this essay had redefined "cannot be explained" as "has not been explained". - there’s an important difference between the two,

Developing claims / counterclaims.

Some students seemed to be stuck in fairly rigid thinking when it came to devising claims / counterclaims. From some students there was a lack of flexibility / creativity in the interpretation of the title. This has made me go back to using more debate in the classroom with my own students, a sort of quasi application of De bono’s thinking hats.

Obviously, difficulty with developing claims / counterclaims can be partly due to a lack of clarity of definitions of key terms, or having dictionary based definitions of key terms.

Problems of identifying or applying RLS.

So this is the question “is X a good RLS for this claim ?”. Some students found it very difficult to identify appropriate RLS to demonstrate their knowledge claims.

Obviously if the claim is not fully understood then it's difficult to find RLS to demonstrate it.

It’s not about the RLS, it’s about the argument that’s being built. I believe that nearly ANY RLS can be used for ANY claim / counterclaim if the argument is well made. I’ll make a future video where we can take claims at random and match them to random RLS to show how any RLS can be used for any claim if you know how to make the argument.

further, and wider, reflections on M23 ToK Essay Session include:

2. Question Choice.

I think that essay # 6 on Methodology is by far the easiest prescribed title in this session, followed by essay # 1 on replicability. I won’t go into why I think they’re the easiest in this video, I made an earlier post & video about this linked here

Looking at all the data points that I have Essay #6 and Essay #1 are the LEAST popular titles in the session. I think that Essay #5 (visual representations) is probably the most popular.

Now, I certainly don’t think that we should tell students which essay to take - it’s meant to be their personal authentic reflection. However, Essay #6 & #1 have really straightforward structures, they don’t have multiple assumptions - they’re just straightforward. I don’t know how we get it over to students that they should consider the straightforward essays as little gifts from the examiners ! I find it particularly frustrating that we shouldn't direct students to questions, but those who need the most help often choose the hardest questions !

3. Use of the 12 ToK Concepts.

Most students with whom I worked were not intentionally using, or referring, to the 12 ToK Concepts. Some of the students didn't seem to be aware that there were 12 core ToK Concepts.

If we put them front & centre it helps to improve focus of the essay, Obviously any of the 12 concepts could be applied to any of the essays. So we need to get students to focus in on 2-3 specific concepts.

I try to get students to identify at least 2 concepts at the beginning of the devising process.

4. Questioning the title for Evaluation Points.

Some students didn’t realise that they can develop strong evaluation points by directly challenging the assumptions in the title.

The most obvious examples of this could be:

Essay #2: what can and cannot be explained may not be exclusive and consistent categories. That which can be explained in one context may not fall into cannot be explained in another context.

And, what we think can be explained today may become ‘cannot be explained’ as we gain new knowledge.

And I also saw this with Essay #4 (“so little knowledge so much power”), where some students didn’t understand that they are meant to challenge Russell’s assertion, that they need to make the argument that we either have a lot of knowledge, or little power, and all possible combinations thereof.

5. Impact of AI, esp ChatGPT.

I started to see content generated by AI coming through, much of this is easy to spot because the AI tends to write with sweeping introductory sections, and uses fairly vague generalisations with lots of hedging words. Obviously we also know it when we see a change in the tone of language used, or the sudden switch to American spelling and grammar.

There’s a lot to say about AI and the ToK Essay, probably in another video, but suffice to say here that currently AI can’t give us anything sufficiently precise to score well on a ToK essay without asking it precise and directed questions. The skills and knowledge required to frame those questions are at least as demanding as just writing the essay yourself. Currently it’s one of those situations in which it is more effort to use the AI than it is just to do it yourself. However, that may change in the coming years.

On 27th February 2023 IB gave guidance that AI generated content can be used, it should be cited just like any other secondary source.

6. Too much description of RLS. - link back to building the argument.

And finally, we come to our favourite old chestnut - description of the RLS. I still saw lots and lots of description of RLS which was largely unrelated to the PT, or knowledge claims being developed within the PT. This remains the most common problem at the Essay Draft stage in my experience, however I think that the latest Subject Report said that most of the essays submitted are now focussed on the PT, so teachers must be working hard to iron this out before final submission - well done teachers !

If you’re a ToK student , and you’re concerned about too much focus on the PT, pick up my e-book How to write the ToK Essay in 6 Easy Steps linked here. The book includes worked examples of how to make an overly descriptive essay more analytical.

So there we have it, reflections on M23 ToK essay session, a bit of learning from the May 23 Essay Session.

I’m looking forward to the Nov 23 titles coming out next week,n Have a great day, stay tok-tastic !

Daniel, Lisbon, March 2023

For other thoughts on ToK Essay:

Why do the best ToK Essays get Mediocre grades?

Unsubstantiated Assertions in The ToK Essay

What is the most important factor in ToK Exhibition ?

A video version of this blog post is available at this link.

The latest ToK Exhibition Exemplars have been published by IB, and we have scrutinised and analysed them to work out what it is they’re looking for so that you can get a great grade in your ToK Exhibition. Today we’re going to tell you what is the most important factor in the ToK Exhibition.

The difference between a good mark and a mediocre mark in the ToK Exhibition mainly rests on one factor, and that one factor is specificity !

Yep, we’ve analysed the IB exemplars, and the examiner’s report, and found that the key factor which moves your marks above 5/10 is specificity.

Let’s look in more detail about what we mean by specificity, we’ll identify 2 main areas of the ToK Exhibition which require specificity.:

Area number 1: Specificity of the object.

Let’s just start with an example: A dictionary is a generic object, however the dictionary that was used to agree a peace treaty between countries A & B in a particular year is a specific object.

The purpose of the ToK Exhibition is for you to explain how ToK is manifested in the world around you, using physical objects. Therefore you need to be able to identify individual objects and say what it is about that object that answers the prompt.

Another example - A Biology textbook is just a generic object, but your IB Biology textbook which made you question the relationship between mind and matter is a specific object.

A pea plant is a generic object, but the first pea plant that Mendel cross pollinated to test a genetic law is a specific object.

I don’t need to go on, you get the idea.

The need for a specific object is why some people think that you have to have a personal link to the objects used. This is a misunderstanding. The objects have to be specific, but you do not have to have a personal link to the object. It’s just that if you do have a personal link you are more likely to choose a specific object. However, a specific object is not sufficient to get a good mark, which conveniently takes us onto our second area of specificity.

Specificity of an is defined by IB as “particular context in time and space is identified” (pg 10 Subject Report, May 2022).

Area number 2: Specificity in what the object contributes to the exhibition.

You have to show how each specific object specifically contributes to the exhibition. Let’s look at an example. If I were answering Prompt #1 “What Counts as knowledge ?”, and I identified 3 specific books, and I argued that each book counts as knowledge because they contain facts, I would not be showing specificity in each object’s contribution to the exhibition. However, if my first object was a historical record going back to 1750 of daily air pressure recorded at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich UK, and I argued that this counts as knowledge because sometimes knowledge is recorded but not observed, and my second object was Darwin’s notes from the Beagle, and I argued that this counts as knowledge because knowledge is sometimes observed but not yet labelled, then I would be showing specificity in the object’s contribution to the exhibition.

This is why I believe that it is best if you identify 3 distinct arguments relating to the prompt, 1 argument for each object. You can see this in this Exhibition commentary I gave last year. In this commentary the objects are not specific enough, but the 3 arguments are clear.

The prompt is “Who owns knowledge ?”, my 3 arguments are:

1. Knowledge Producers own knowledge.

2. Knowers own knowledge.

3. Intention (or context) owns knowledge.

Another example is seen in this recent commentary that I gave.

The prompt is “What counts as knowledge ?”. My 3 arguments are:

1. Knowledge is that which has meaning for a restricted community of knowers.

2. Knowledge is that which has meaning for everyone and anyone.

3. Knowledge is that which only has meaning for the individual.

Ensuring that you clearly explain the knowledge link between that specific object and the prompt is important. That link should be different for each individual object, and it should be a knowledge link, if you want to get a high mark. There are 2 points to bear in mind here:

Firstly, don’t repeat the same link for all 3 objects. The link needs to be different for each individual object.

Secondly, and more importantly, the link needs to be a knowledge link, not a real world context link. Let’s look at another example. If you were answering the prompt “What is the relationship between knowledge and culture?”. Your object may be an auto-rickshaw used in a UK advert promoting tourism to India. The link should not be limited to the observation that the auto-rickshaw is characteristic of transport in India. It needs to go on to make a more generalised knowledge point. Such as individual objects can represent wider bodies of knowledge or meaning particularly when those meanings are associated into a system like a culture.

So, there we have it - keep it specific, and you will improve your chances of getting high marks on the ToK Exhibition.

Enjoy your ToK learning, stay tok-tastic my friends.

Daniel, Lisbon, Feb 23

Other ToK Exhibition Resources:

Latest ToK Commentary : What counts as knowledge?

What are the ToK Exhibition Examiners thinking?

ToK Exhibition Commentary - what counts as knowledge ?

Here's the latest attempt at a ToK Exhibition written after the analysis of the latest Exemplars (uploaded to the PRC on 7th Feb 2023), and a re-reading of the May 2023 subject report. I was trying to focus on developing the specificity of the object links, and contributions to the Exhibition.

Prompt #1: What counts as Knowledge ?

My first object is a childhood note from me to my brother written in a code that we devised as children. The code is meant to be a secret language between my brother and I. The note conveys knowledge which is exclusive to the two of us as the code was devised by, and only understood by, the two of us. The note counts as knowledge because it contains meaning which can only be interpreted by a specific community of knowers. Examples of similar knowledge are the designated areas used in the UK Shipping Forecast, code signs used by military or police personnel, or symbolic meaning within a youth subculture like the Mori Kei in Japan . The significance of the exclusivity of such knowledge is that it either evolved, or was devised, for a specific purpose - communicating meaning in an abbreviated, or telegraphed form. The exclusivity of the knowledge could be one of the purposes of its design (as is the case with the code that I devised with my brother), or it could be an unintended function of the knowledge (as is the case with the areas in the shipping forecast). This counts as knowledge because meaning is derived from membership of a specific group of knowers.

The note is included in the exhibition because what counts as knowledge is both contextual and purposeful. Taken out of context our code becomes little more than a set of squiggles on paper. The context of knowledge comprises those who produce the knowledge, those who acquire the knowledge, and the purpose of the knowledge. Without an understanding of context (usually acquired through membership of a group of knowers) the knowledge can be misinterpreted, or even meaningless (ie no longer knowledge).

However, knowledge which is created to remain exclusive can be understood by knowers beyond the target community if they develop either a deep understanding of the context, the purpose, or tools of deciphering the code. This indicates that what counts as knowledge may not be the content / meaning, but may be the context and purpose of the knowledge community.

The second object is an MRI scan of my left knee, showing a tear in a ligament. The MRI scan was looked at by 2 unrelated medical professionals working in separate hospitals, both medics interpreted the scan in exactly the same way. This image counts as knowledge as it is knowledge produced by a community of knowers who share a standardised method of knowledge production. This community of knowers also share a standardised threshold for what constitutes knowledge. However, what sets this knowledge apart from Object 1 is that this knowledge is designed to be understood beyond it’s originating community of knowers. The MRI scan is knowledge produced using the scientific method, as such it counts as knowledge because of its method of production, its objectivity, reliability, validity and universality. As such the MRI scan is knowledge based on facts.

The MRI scan is included in the Exhibition because some knowledge is not based on opinion, nor meaning which is solely specific to a community of knowers. Such knowledge is produced using methods which are designed for universality across community of knowers, and replication for the purposes of validation, Eg The scientific method. The generalisability, and aspiration for universality, of such knowledge is why this counts as knowledge. This is knowledge which has standardised meaning regardless of context, the knower, nor the purpose of the use of the knowledge. Human and Natural Scientific knowledge should be understood, and interpreted, in the same way regardless of the context of the knower. This is particularly important when we are considering knowledge pertaining to the organisation and maintenance of human life such as engineering, medical and economic knowledge.

However, the objectivity of such knowledge may detract from the individualised experience of the knower. Whilst two MRI scans may show the same condition in two separate people the individuals may experience that condition in very different ways. Knowledge which is designed for objective generalisability runs the risk of losing the meaning of that knowledge which is specific to the individual knower.

The third object is a ticket from a music concert that I attended in May 2022. At the concert I experienced strong emotions of elation, freedom and near transcendence. This was a ‘peak experience’, the closest that I have come to a sublime state. The ticket counts as knowledge as an experience which was the most truthful that I have experienced, but could not be externally validated, nor necessarily shared with other knowers.

Internal knowledge, sometimes called self knowledge represents a form of internal truth. This counts as knowledge to the knower as it can be a very strong form of knowledge.

However, it is not necessarily known to other knowers, nor is it necessarily validated or even agreed by others. As such the ticket is included in this Exhibition because it represents a wholly individual form of knowledge unlike objects 1 and 2. Such internal knowledge can include emotions, experiences, intuition and memories. The internal nature of such knowledge can be difficult to communicate to other knowers, making external validation even more difficult. However, such internal knowledge can have significant influence on the interpretation, explanation and perspectives that knowers form regarding new externally produced knowledge. For example, I will now be more receptive to knowledge which is aligned with the musicians who played at the concert (eg adverts using music from the same band).

Arguably values are a form of such internal knowledge, they may have external labels but are experienced at a near internal level. As values are the basis of interpretation, and perspectives the consideration of such internal knowledge is important if we are to understand what counts as knowledge. Forms of knowledge production designed for a wider community of knowers are influenced by the values and perspectives of the knowledge producer. For example, bio-chemists have to decide which disease to study when formulating treatments, this initial decision can be influenced by values.

Therefore, it is argued that internal, unvalidated, knower specific knowledge (aka “Truth”) is the basis of all knowledge, and therefore is the essence of what counts as knowledge.

I have many more ToK Exhibition Resources, including:

ToK Exhibition What do we know in Feb 2023?

ToK Exhibition Skills Builder Part 1

ToK Exhibition Skills Builder Part 2

What are the ToK Exhibition Examiners thinking?

Daniel, Lisbon, Feb 23

ToK Exhibition - what do we know Feb 23?

In Feb 2023 IB posted 10 new Exemplars of ToK Exhibitions. I've closely analysed them to see if we can learn anything new from them, or if they further confirm things that we already know. I have summarised the main findings in the table linked below.

What we Know - Exhibition Feb 23

3 key findings:

Specificity of objects, and specificity of knowledge links between the objects & the IA prompt are key to doing well.

Three perspectives / arguments is key to developing the specificity required in the link and justification for inclusion of the object.

There's still some ambiguity as to whether objects symbolising knowledge / meaning / culture are allowed.

There are many other findings, clarifications and confirmations in the document - check it out.

If you have any thoughts, or corrections, I'd love to hear them in the comments below.

Have a great day,

Daniel, Lisbon, Feb 23

Further information on The ToK Exhibition can be found at:

Ethics & Technology.

When thinking about the possible ethical issues arising from technology in a ToK context I start from the perspective of ethics rather than technology. In doing so I will be asking 4 big questions:

What are the potential ethical issues arising from technology?

Where do these ethics and technology issues sit on a ‘good-bad’ continuum?

What are the implications of these ethics & technology issues for the construction and acquisition of knowledge?

How might these ethics & technology issues evolve in the future?

What are the potential ethical issues arising from technology?

We tend to think of ethical issues arising from technology in modern terms, ie issues arising from modern digital technologies. However there have been ethical issues arising from technology since humans first started to utilise technology. In the modern age such issues rose to greatest prominence during the first era of industrialisation in the 19th Century.

I will look at ethical issues arising from technology through 4 main lenses / perspectives. Each perspective has both positive and negative ethical consequences within it.

4 lenses that have ethical consequences arising from the application of technology:

Accessibility

Health, productivity and fulfilment.

Diversification - Homogenisation

Privacy - Autonomy - Control

Accessibility.

Positive ethical consequences of improved access afforded by technology.

Technology both increases and decreases accessibility across a wide range of fields, and in multiple ways. A starting point to think about this is that technology should increase our capacity to manipulate the environment. The outcomes of such manipulation in terms of accessibility will reflect the value basis of those in charge of the technology. Whether this is a negative, or positive, ethical outcome will also largely depend on the value basis of those making the judgement. Let’s take the application of technology in a mediaeval village as a real world example. The application of technology to crop production (eg ploughing, irrigation, crop rotation etc) increases the yield of production. Thus increasing access to food, and the time available to residents to access other ways to spend their time. There are subsequent consequent improved access improvements such as access to healthcare, culture, further technological innovation etc.

The most obvious improvements in access realised by modern technologies are access to knowledge acquisition and knowledge production. The development of public libraries, public education, and the internet have significantly improved the access that people have to knowledge acquisition. The development of universities, and more recently Web 2.0, significantly improves the access that people have to knowledge construction.

Schutz: The Social Distribution of Knowledge.

The positive ethical benefits of such improved access are wide ranging, and potentially profound. The expansion of human and civil rights seen in many areas of the world can be understood as being augmented by the improved access to knowledge realised by technology. In his article The Well- Informed Citizen: An Essay on the Social Distribution of Knowledge Alfred Schutz explains how improved access to knowledge changes the classification of an elite ‘expert’ group who are afforded the right to produce ‘socially approved’ knowledge (that is knowledge afforded prestige and influence). Technology allows more people to join this group, adding a more diverse set of perspectives to socially approved knowledge. Schulz uses the models of social identity theory from Social Psychology to understand the possibly liberating effects that wider knowledge access can have for individuals in breaking down in group-out group stratification. Further, Schulz explains how wider access to knowledge increases people’s opportunities to question taken for granted assumptions, and therefore increasing the potential to develop ‘better’ knowledge, ideas that have built upon, and evolved from that which is pre-existing.

Friedman: The World is Flat.

Schutz rather prophetically wrote his article in 1946, many of his ideas were updated in 2005 by Thomas Friedman in his book The World is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty First Century. Friedman describes how technology (mainly Web 2.0 tech) has increased access to knowledge acquisition and construction which, in turn, has enabled those in developing countries to compete financially, technologically, and culturally with those in the developed world. Here we see the argument that access afforded by technology has significant positive ethical consequences.

Schutz rather prophetically wrote his article in 1946, many of his ideas were updated in 2005 by Thomas Friedman in his book The World is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty First Century. Friedman describes how technology (mainly Web 2.0 tech) has increased access to knowledge acquisition and construction which, in turn, has enabled those in developing countries to compete financially, technologically, and culturally with those in the developed world. Here we see the argument that access afforded by technology has significant positive ethical consequences.

Negative ethical consequences of improved access afforded by technology.

The most common concern raised with the increased access that technology allows is applied to digital technologies - the digital divide. We will come to that later in this section, but let’s first take a step back and consider the wider knowledge implications of increased access to technology.

The argument for the positive ethical benefits of increased access to technology is essentially that more of things (knowledge & its consequences) is a good thing. However, this doesn’t account for the context within which this change occurs, specifically the values and purpose of the wider society. That increased access will have outcomes which are, arguably, largely shaped by the value structures and power relationships of the wider society within which they operate. Namely, the value structure of the wider society. If the value structure is one in which power is used to restrict the freedoms, or privacy, of the individual then this could be reflected in the wider access to knowledge afforded by technology. Not only does the mass populace have more access to knowledge, but powerful actors now have more access to the thoughts and behaviours of the population. We will come back to this in the section on privacy.

The concept of ‘more’ isn’t necessarily a positive ethical outcome, let’s go back to our mediaeval village. After the application of agricultural technology the people have more time to do things other than farming. However, if there’s a power structure which can direct how people spend their time (eg a Lord of the Manor) this extra time could be used for negative ethical outcomes such as warfare, environmental destruction etc.

The Digital Divide.

The digital divide refers to the unequal distribution of technology and internet access between different groups of people globally. The divide creates a gap between those who have access to the knowledge resources opened up by the internet and those who do not, leading to unequal opportunities for growth, development, and success. For example Northern Europe has an ‘internet penetration’ (people who have access to the internet) of 95% whilst Africa has an ‘internet penetration’ of approximately 40% (“List of countries by number of Internet users”)

The digital divide affects individuals from different regions, socio-economic backgrounds, age groups, and cultures. People who live in rural areas, low-income communities, and developing countries often lack access to technology and the internet. This limits their opportunities for education, job training, and accessing information, which can lead to lower wages and limited opportunities for social and economic mobility.

The digital divide also affects businesses, as those without access to technology may struggle to compete in the global market. Moreover, it perpetuates existing inequalities, such as gender and race, as marginalised communities are often the ones who lack access to technology and internet.

The Digital Divide is an example of technology widening the gap of power between those with and without access to the technology. This is a recurring theme that we will see arising from many different types of technology across history.

Health, productivity and fulfilment.

I am rather uncertain about including a section on the applied ethical effects of technology as I run into danger of describing the real world ethical effects of technology rather than focussing on the ethical effects of technology on knowledge acquisition, construction and interpretation. However, as this is somewhat a false division, and students need to draw upon real world examples for both ToK assessments, I’ll go ahead and include this section anyway.

At prima facie level the immediate effect of the application of technology in area of life should be to increase productivity - this applies equally to the production of knowledge as it does to the production of ceramic vases, cars or pizzas. This increase in productivity has significant ethical effects. There is a long tradition of writers (eg sociologists, artists, economists etc) describing the negative effects of technology in the workplace. There is a significant body of research on the alienation and deindividuation experienced in the industrialised workplace. In his paper on Technology and Human Relations Carleton Coone argues that increased application of technology requires a more pressing focus on designing for human relations if we are to avoid the negative effects of that technology (such as alienation). Students can review the paper (referenced below) for real world examples.